The stories of three file systems

There are many many kinds of file systems out there. Engineers must make tradeoffs between performance, compatibility, and human factors. Today, let’s go back to 2001 (slightly before you were born!?) to look at Apple iPod’s file-system and the sad story of ReiserFS. Today, listening to music means streaming from Spotify or Youtube. Storage is cheap and big. You can buy a 256GB microSD card at a convenience store for under 500 NTD. But in 2001, the digital storage landscape looked completely different. In 1997, people began to carry bulky CD player to the beach (+ multiple CDs in a case). Sony’s “CD Walkman” was a cool new toy. Listening to music was no longer an indoor activity. Flash memory in 2001 was expensive and tiny. The first USB flash drives (invented in Israel) offered only 8MB of storage. Portable music players based on flash memory could store about a dozen songs at most. Flash memory had a big advantage though: it was solid-state, meaning no moving parts. You could drop a flash-based player and it would keep working. Hard drives offered far more capacity but came with serious drawbacks. A mechanical hard drive contains spinning magnetic platters and a read/write head that moves across them. If you dropped a hard drive or shook it while it was spinning, the head could crash into the platter and destroy data. No company was able to produce a truly portable music player with a hard drive that could survive being carried in a pocket. In 2001, Steve Jobs stood on stage and pulled out a strange device from the pocket of his jeans, and said: “1,000 songs in your pocket.” This was the original iPod. Apple used a tiny 5GB Toshiba mechanical hard drive. The drive was fragile. Drop the iPod while it was playing and you could kill it. But Apple solved this with clever engineering: the iPod would spin up the drive, rapidly load about 30MB of music into RAM, then immediately stop the spinning to minimize the vulnerability. As long as the drive was not actively spinning, the device could survive some shocks. That “1,000 songs in your pocket” slogan was quite impressive in 2001. For the first time, you could carry your entire music library without a stack of CDs or a bulky player. The iPod sold over 400 million units and lay the foundation for iPhone, which launched in 2007. But there was a problem. The iPod initially shipped formatted with the HFS+ file-system (same as Mac OS X). At that time, Windows computers represented 97% of the market, and Windows could not recognize HFS+. Apple needed a solution that worked for both Mac and Windows users without maintaining two separate product lines. Apple was forced to adopt FAT32 (File Allocation Table 32-bit), a file system that dates back to 1996 as an extension of the much older FAT system from MS-DOS. Let’s contrast FAT32 with ext2, which we studied in lecture. In ext2, each file has an inode that contains metadata (permissions, timestamps, size) and pointers to data blocks. The inodes are stored in a dedicated inode table, and you locate a file by first finding its inode number from a directory entry, then reading that inode to get the block locations. FAT32 works differently. Instead of a separate inode table, FAT32 stores all its block allocation information in a single large table at the beginning of the disk called the File Allocation Table (FAT). Here is how it works: For example, suppose you have a file called This linked-list-traversal style means reading a file requires multiple lookups in the FAT table, especially if the file is stored in non-contiguous clusters. In ext2, the inode directly stores pointers to the first 12 data blocks and we can directly read them without traversing a chain. The biggest advantage of FAT32 is universal compatibility. Almost every OS can read and write it without special drivers. This is why FAT32 remains standard today for UEFI boot partitions in your PC and SD cards in cameras. However, FAT32 has many limitations: Apple formatted every iPod as FAT32 at the factory. But this is not the end of the story. When a user connected an iPod to a Mac for the first time, iTunes would silently reformat it to HFS+. Windows users never saw this happen. Their iPods stayed as FAT32 forever. But hey, if FAT32 is fine for iPod, why did Apple reformat iPods to HFS+ when connected to Macs? The answer is probably to save battery life. The iPod had a slow ARM processor and only 32MB of RAM. Spinning the mechanical hard drive was power-hungry and made the iPod vulnerable to shock damage. Every second the drive spent spinning was a second it could be dropped and have data corrupted. To maximize battery life and minimize mechanical risk, the iPod used an “suck-up” buffering strategy: spin up the disk once, load about 30MB of upcoming songs into RAM as quickly as possible, then immediately stop the disk. The remaining 2MB of RAM was for the OS. The drive would only spin again when the buffer was nearly empty, which for most users meant 20 to 30 minutes of silent operation between spin-ups. HFS+’s efficiency reduced the disk’s vulnerable timespan. On the other hand, on FAT32, if your song file is spread across 10 non-contiguous clusters, the system must read 10 different FAT entries and seek to 10 different disk locations. On a slow processor with a mechanical drive, this sucks up more battery life. HFS+ uses B-trees to index files. A B-tree is a self-balancing tree structure where each node can have many children. This keeps the tree shallow. Instead of traversing a linked list, HFS+ can find any file’s blocks in logarithmic time. This typically means just 2 to 3 disk reads even for large directories. The iPod could load songs into memory faster and the drive could spin down sooner. Apple released the iPod Nano in 2005 with flash memory instead of a mechanical drive. Flash memory has no moving parts. Your data remains ok even if you shake it. Nowadays, your phone could easily have 256GB flash memory at the size of a 1 NTD coin. But do you even store “1,000 songs in your pocket”?? While Apple was optimizing for 5MB music files on fragile spinning disks, Linux servers were dealing with a different problem: millions of tiny files. Web servers, email servers, and code repositories store a lot of files smaller than 1KB. As you learned in class, file systems allocate disk space in fixed blocks, usually 4KB. When you save a 100-byte configuration file, it still consumes an entire 4KB block. The remaining 3996 bytes cannot be used by other files. This waste is called internal fragmentation. In the early 2000s, kernel developer Hans Reiser created ReiserFS to solve this problem. Reiser studied computer science at UC Berkeley and had strong opinions about how file systems should work. ReiserFS, like HFS+, was built on B-trees. But Reiser added a feature called tail packing. Instead of giving small files their own blocks, ReiserFS stored the data directly inside B-tree leaf nodes alongside the metadata. If you had ten 100-byte files, ReiserFS could pack them all into a single 4KB disk block. This eliminated internal fragmentation for small files and increased a lot of usable storage space. By 2002, ReiserFS had become the SOTA file-system and was used by many companies. In software engineering, the bus factor measures how many team members would need to disappear for a project to collapse. FAT32 has an infinite bus factor because the specification is public and thousands of engineers across dozens of companies have implemented it independently. ReiserFS had a bus factor of approximately one, because Hans Reiser and his small company in Russia were the only code contributors to ReiserFS (while other file-systems in Linux kernel were combined efforts from more developers). Reiser was a genius but he frequently clashed with Linux kernel maintainers (who were equally smart). Hans Reiser had a miserable marriage with his Russian wife, Nina Reiser. In 2006, he murdered his wife and was sent to prison. ReiserFS development stopped. ReiserFS was deprecated in 2022 and removed entirely from Linux in 2024. In prison, Hans learned social and communication skills. He apologized to the Linux community, and acknowledged his team members’ contributions. Data Structure matters: Both HFS+ and ReiserFS used B-trees to solve the problem of slow disk access. The iPod’s choice between FAT32’s linked lists and HFS+’s B-trees had measurable impact on battery life and how quickly the fragile mechanical drive could spin down. Compatibility matters: FAT32 has a 4GB file size limit, no journaling, and inefficient lookups. ReiserFS had better space efficiency and faster small-file access than the SOTA, ext3. Yet FAT32 is still here today while ReiserFS is gone. The iPod succeeded partly because it conformed to the commercial reality: clashing with Windows means killing yourself. But now, Apple intentionally makes itself Microsoft-incompatible to lock in people into the Apple ecosystem. think Air Drop. 🤨🤨🤨 This semester we spent only one week on file systems, but the world of data storage is far more fascinating than what we could cover. If you found today’s stories interesting, consider taking Advanced Storage Systems next semester taught by me. We will explore the design and implementation of modern storage systems, and cutting-edge research that shape how operating systems manage data. You will learn by reading, analyzing, and discussing classic and contemporary research papers. We will cover core topics ranging from I/O devices and file system fundamentals to distributed storage and sandboxing techniques. You will learn why Google built their own file system (GFS), how Copy-on-Write filesystems like Btrfs and ZFS work, and how modern cloud storage systems handle petabytes of data. If you enjoyed thinking about data structures and tradeoffs in this lecture, you will find an entire semester of similar engineering challenges waiting for you. Welcome to the wonderful world of system research. I wrote this handout after listening to the Co-Recursive podcast. Former Apple engineer David Shayer talked about Apple’s big secret in this episode (Do you know iPod used to be a spy device for nuclear radiation detection??). The story of Hans Reiser is from this episodeThe iPod

The Portable Music Problem

“1,000 Songs in Your Pocket”

FAT32

song.mp3 that occupies three clusters: 100, 215, and 316. The directory entry for song.mp3 stores the starting cluster number (100) along with the filename and file size. When you read the file:

Why Bother with HFS+?

ReiserFS

Tail Packing

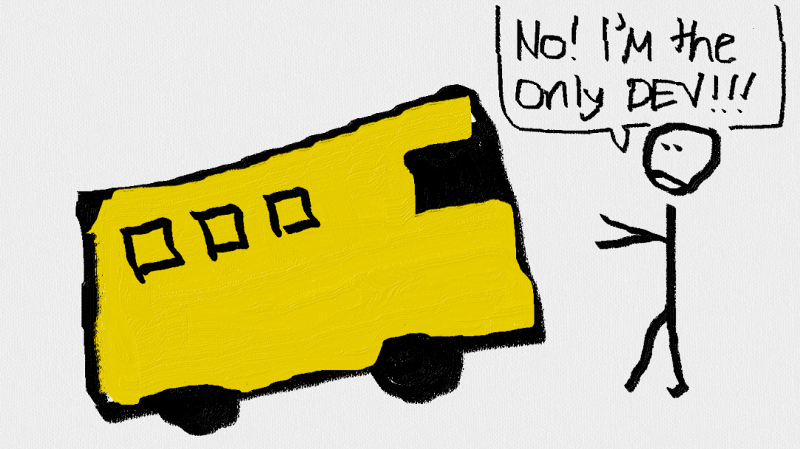

Bus factor = 1

Bring-home lessons

Want to Learn More?